Question Session 03

These are the recordings of the live online whole-class question session. They are usually available on the day after the session. (You may need to refresh this page to make them appear.)

If the video isn’t working you could also watch it on youtube. Or you can view just the slides (no audio or video).

This recording is also available on stream (no ads; search enabled).

If the slides are not working, or you prefer them full screen, please try this link. The recording is available on stream and youtube.

Notes

How to Write the Essay

Answer the question. Your answer may be nuanced. And feel free to focus on any aspect of it.

The question is not about you. Do not give an opinion. Support your conclusion with evidence or argument.

You can use any reasonable claim from another area of philosophy or another discipline as a premise in your essay, but you must clearly state any premises you use (thank you Louis!). For example, you may take as a premise that actions are distinct from judgements and other mental events.

How can I avoid being too descriptive?

Matt’s tip: Why does each of the views pose a puzzle for the other size?

Diogo’s tip: Don’t try to explain everything. If you find something fishy, focus on that.

Does I need to be original? Not in 500 words.

How much should I read?

- first draft: as little as possible (yyrama essential readings only)

- second draft: as much as possible

Moral Intuitions and the Dumbfounding-Disengagement Puzzle

In Conclusion: Yet Another Puzzle I phrased the Dumbfounding-Disengagement Puzzle like this:

Why are moral intuitions sometimes, but not always, a consequence of reasoning from known principles?

Emily H, Anna R, and Svenja offer a series of objections (thank you!). This motivated the following clarification:

Reasoning from known principles cannot directly influence moral intuitions.

Reasoning from known principles can modify how events are interpreted, which aspects are attended to, and how actions are categorised, and so indirectly influence moral intuitions.

I take moral disengagement to show that moral intuitions are consequences of reasoning in this sense:

People sometimes anticipate that they will have certain moral intuitions and reason from known principles in order to avoid having them.

What Are Moral Intuitions?

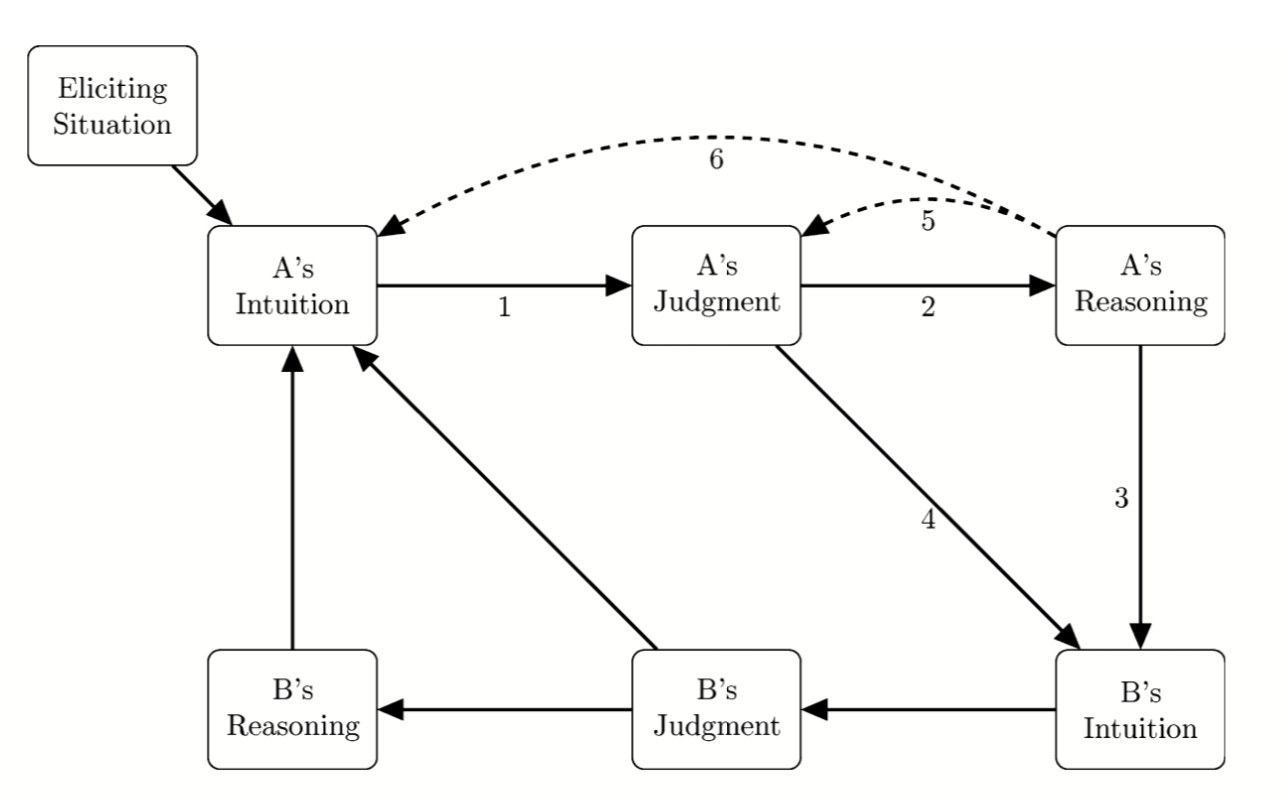

Svenja made an objection about moral intuitions and the Social Intuitionist Model of Moral Judgement presented in Haidt & Bjorklund (2008) (see figure below;1 this was discussed in Moral Disengagement: Significance).

Figure: The Social Intuitionist Model of Moral Judgement Source: Haidt & Bjorklund (2008, p. figure 4.1)

Figure: The Social Intuitionist Model of Moral Judgement Source: Haidt & Bjorklund (2008, p. figure 4.1)

On this model, moral intuitions cannot be unreflective judgements (because on that definition, intuitions are judgements; it would make little sense to depict them as causes of judgements).

Nor, on this model can moral intuitions be ‘strong, stable, immediate moral beliefs’ (Sinnott-Armstrong, Young, & Cushman, 2010, p. 256). For then it would make sense to regard them as causes of judgements, but probably only through processes of reasoning. Further, Haidt & Bjorklund (2008, p. 181) assert that

‘moral judgment is a product of quick and automatic intuitions.’

Since a belief cannot be quick (nor slow), Haidt and Bjorklund cannot be thinking of moral intuitions as Sinnott-Armstrong et al. do.

Conclusion: Different researchers use the term ‘moral intuition’ for different things. It is not always easy to work out which things they are using it for.

Additional Sources on Huebner, Dwyer, and Hauser

Emilie requested additional sources which oppose the arguments offered in Huebner et al. (2009) (discussed in PS: Does emotion influence moral judgment or merely motivate morally relevant action?).

Ollie suggested Ugazio, Lamm, & Singer (2012). They aim to ‘uncover the mechanisms by which emotions exert their influence on moral judgments’ (p. 587) by comparing the effects of different emotions—anger and disgust—on responses to four scenarios involving moral violations.

Decety & Cacioppo (2012) explicitly targets Huebner et al. (2009). They conclude that ‘moral reasoning involves a complex integration between emotion and cognition that gradually changes with age.’

Piazza, Landy, Chakroff, Young, & Wasserman (2018) conclude from a review of evidence that there is at best weak evidence for effects of feelings of moral judgement. Although Huebner et al. (2009) would probably welcome this conclusion, Piazza et al.’s approach is different from Huebner et al.’s.

Glossary

According to Sinnott-Armstrong et al. (2010, p. 256), moral intuitions are ‘strong, stable, immediate moral beliefs.’

References

-

I updated this figure to the version in Paxton & Greene (2010) since the recording; the previous version reproduced from Haidt & Bjorklund (2008) had some arrows pointing in the wrong direction. ↩